Heron MJ1

by Patrick Harlow

Early Concept sketch of a targa-top Heron MJ1.

Plug under construction.

The prototype being quality inspected by the local cat. |

In the eary '80s Ross started work on what would be his biggest adventure yet. Using his sketchbook he started to design what would become New Zealand's most successful production car. Initially, it was never intended to be sold as a brand-new drive away car. Instead, it was supposed to be a factory assembled kit-car. The 80s was a boom period for the kit-car industry with over 35 different cars being produced throughout the country. The idea for a fibreglass monocoque had come to him when they were building the first Heron Spraymaster. By this time, he had learnt enough about fibreglass to believe that he was quite capable of building a fibreglass monocoque body/chassis at least as strong as an equivalent built using steel. Fibreglass did not require the use of huge industrial steel presses to stamp the panels, so it was the ideal material for small volume production. Additionally, with fibreglass being ‘laid up’ in multiple layers it was relatively easy to add strength to potential weak spots by either making the fibreglass thicker or by adding Kevlar and/or stainless steel mesh. He calculated that to get the same strength as steel, the thickness of the fibreglass had to be multiplied by three. Ross also developed the “Heron patented stainless-steel mesh” method of adding additional strength and stiffness to panels that supported high load components like the suspension. Fibreglass is very strong over a large area but has little localised strength. The use of stainless-steel mesh embedded in the fibreglass allows the load to be spread over the area determined by the size of the mesh or number of layers. |

|

The donor car he decided to use was the Skoda 110. Despite being a bit of a joke at that time, they did not deserve their bad press. Having worked on many of these cars in his shop he knew they were really a good little car. The Skoda front suspension had a cross member with wide mounting points, unequal length wishbones and disc brakes, ideal to give plenty of room in the footwells of a mid-engine car. The Skoda transaxle and rear suspension also had wide mounting points and the transaxle was a very sturdy four-speed unit. With plenty of second-hand cars around Ross knew that he would not have the additional cost brought about by the 40% sales tax that was levied on new cars at the time. The MJ1 would be the first project in a long time that Bob Gee would have no physical input. Back then, he was very busy with the Spraymaster Mk2 and building the giant moulds required for that project. This time it would not be Ross and Bob, instead, it would be Ross along with his ‘Man Friday’ – Chris Cooke. Pete Guilford was the third member of the team that met in the Baker Shed to build the moulds with Paul McDiarmid of Rotorua Fibreglass stepping up to do the fibreglassing. By the start of 1983, the Prototype was fully road worthy. In the early ‘80s, the only thing that was required before the car could be registered, was a Warrant of Fitness (WoF). Early in 1983 Ross was approached and asked if he wanted to show his Heron MJ1 at the Auckland 1983 Motor Expo scheduled for July. With the excitement of the prototype being finished, Ross decided to put three Herons on display. Having no idea what was going to happen at the show Ross promised that, if by the end of the weekend, they had four orders, he and Bev would buy his team of volunteers, Peter Guilford, Derrick Canty, Allan MacKay and Wayne Maisey dinner on the Sunday night. After the show, Ross was stunned by the success of the weekend, in his pocket was a notebook which held 350 names of people that had expressed an interest in buying a car. These morphed into 20 definate orders with cash deposits. Ross was pretty sure that he and Chris could build four or five cars a year. Demand was already outstripping what he could supply. He was going to need to employ more staff, which meant he was going to somehow have to cover all their wages until the money from car sales started to roll in. However, before he started gearing up for production, he was convinced by Frank Hart, of Summit Engineering, that a car this good should only be sold brand new, and turnkey. Frank even offered to become the projects main financial backer and offered to purchase two-thirds of the Heron Company. Ross quickly learned the downside to this arrange as Summit having the majority vote started to make changes. One of the many changes that Summit made was to have the original 1.6-litre motor changed to a brand new 2.0-litre Fiat motor. Ross had designed the car around the 1.6-litre unit, and the 2.0-litre meant that parts would have to be beefed up and possibly changed to take the greater power. Summit Engineering was looking for a quick return on their investment, so any development work had to be done while the car was in production. As a consequence of this imperfect design/development process, cars left the factory that Ross knew would return under warranty. He was not happy with this situation but being the minority shareholder, he had lost control. The situation between Ross and Summit grew tense and despite the last couple of cars being profitable, Summit decided to back out of the car business, as they were not getting a reasonable return. Ross opted to buy back the rights to the Heron and the moulds. Production officially stopped early in 1985. Around 25 cars were produced, most of which have suvived to this day. |

Ross Baker with Chris Cooke(right) in 1983. Behind the prototype is the GT MK4 which was at this stage still unfinished.

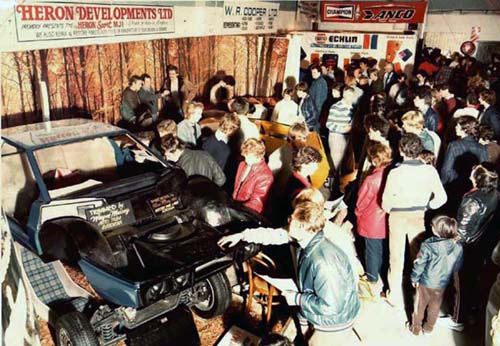

Crowds around the Motor Expo stand.

The finished prototype by the old Rotorua pumphouse in 1983. |

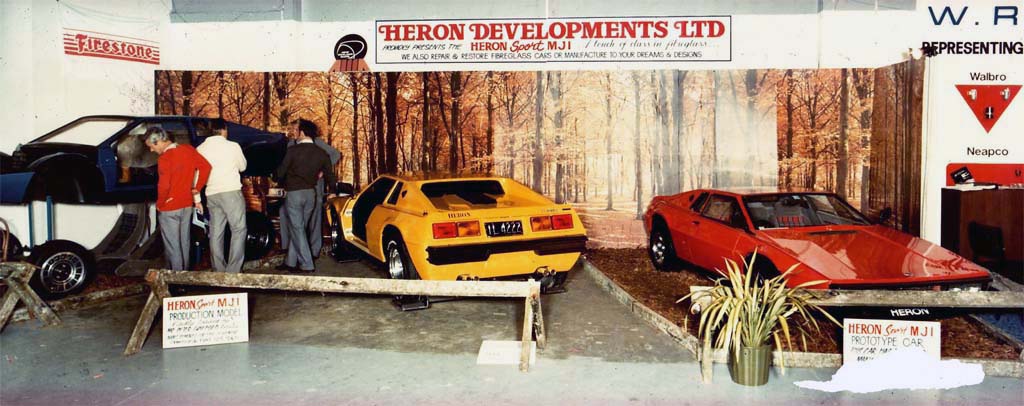

Three cars at the 1983 Motor Expo before the crowds arrived.